Cover Story, April 2024: In Progress–Iratxe Klaas & Klaas van Gorkum

Tue, Apr 2 2024The April 2024 monthly Cover Story “In Progress–Iratxe Klaas & Klaas van Gorkum” is now up on our homepage: www.lttds.org (after April 2024 this story will be archived here).

“On the occasion of their participation in Ten Thousand Suns, the 24th edition of the Biennale of Sydney, April’s Cover Story spotlights Iratxe Jaio & Klaas van Gorkum, and The Margins of the Factory, the solo exhibition of the duo’s work that Latitudes curated in 2014.” → Continue reading

Cover Stories are published monthly on Latitudes’ homepage featuring past, present, or forthcoming projects, research, texts, artworks, exhibitions, films, objects, or field trips related to our curatorial projects and activities.

- Archive of Monthly Cover Stories

- Cover Story, March 2024: Dibbets en Palencia, 4 March 2024

- Cover Story, February 2024: Climate Conscious Travel to ARCOmadrid, 1 February 2024

- Cover Story, January 2024: Curating Lab 2014–Curatorial Intensive, 2 Jan 2024

- Cover Story, December 2023: Ibon Aranberri, Partial View, 2 Dec 2023

- Cover Story, December 2023: Ibon Aranberri, Partial View

- Sat, 2 Dec 2023

- Cover Story, November 2023: Surucuá, Teque-teque, Arara: Daniel Steegmann Mangrané, 2 Nov 2023

- Cover Story, October 2023: A tree felled, a tree cut in 7, 2 October 2023

- Cover Story, September 2023: The Pilgrim in Ireland, 6 September 2023

- Cover Story, July–August 2023: Honeymoon in Valencia, 1 July 2023

- Cover Story, June 2023: Crystal Bennes futures, 1 Jun 2023

- Cover Story, May 2023: Ruth Clinton & Niamh Moriarty in Barcelona, 1 May 2023

- Cover Story, April 2023: Jerónimo Hagerman (1967–2023), 1 Apr 2023

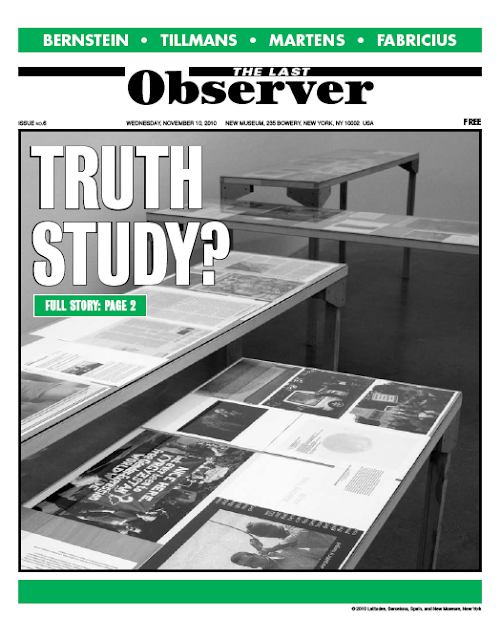

Wolfgang Tillmans’ “Truth Study Center (NY)” (2010)

Mon, Dec 11 2023Forward ten years. In 2021, the interview “Is This True or Not?” was included in the 352-page reader “Wolfgang Tillmans: A Reader” (ISBN 9781633451124), published on the occasion of his retrospective “To Look Without Fear” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and edited by Roxana Marcoci and Phil Taylor – see pages 171 to 173.

- Night at the (New) Museum, 11 Dec 2010

- At Last...The Last Newspaper catalogue!, 10 Dec 2010

- 'THE LAST OBSERVER' AVAILABLE NOW! #6 issue of the 10 Latitudes-edited newspapers for 'The Last Newspaper' exhibition, New Museum, 10 Nov 2010

- Max Andrews reviews in frieze: ‘A Provisional History of the Technical Image, 1844–2018’ (LUMA Foundation, Arlès) and Pere Llobera's ‘Acció’ (Bombon Projects, Barcelona) and ‘Kill Your Darlings’ (Sis Galería, Sabadell), 4 January 2019

Helene Romakin interviews Latitudes for artfridge.de

Tue, Oct 8 2019- Conversation for the exhibition catalogue "Limits to Growth" by Nicholas Mangan (Sternberg Press, 2016) 31 October 2016

- In conversation with Lucas Ihlein for Artlink Magazine 5 September 2016

- Witte de With and Spring Workshop's 'Moderation(s)' publication 'End Note(s)' is out! 5 March 2015

- Interview with Nicholas Mangan in Mousse Magazine #47, February–March 2015 11 February 2015

- "Focus Interview: Iratxe Jaio & Klaas van Gorkum", frieze, Issue 157, September 2013 14 September 2013

Cover Story—April 2018: Dates, 700 BC to the present: Michael Rakowitz

Tue, Apr 3 2018The April 2018 monthly Cover Story "Dates, 700 BC to the present: Michael Rakowitz" is now up on Latitudes' homepage: www.lttds.org

"As Michael Rakowitz’s fourth plinth commission is unveiled in London’s Trafalgar Square, this month’s cover story image revisits Return (2004-ongoing) a related project by the artist that also speaks about the turbulent history of Iraq. And dates. In London, Michael has deployed thousands of date syrup cans to make a 1:1 scale recreation of Lamassu, the fantastic winged bull that graced the gates of the city of Nineveh from 700 BC until it was destroyed by Isis in 2015."

—> Continue reading

—> After April it will be archived here.

Cover Stories' are published on a monthly basis on Latitudes' homepage and feature past, present or forthcoming projects, research, writing, artworks, exhibitions, films, objects or field trips related to our curatorial activities.

RELATED CONTENT:

- Archive of Monthly Cover Stories

- Cover Story – March 2018: "Armenia's ghost galleries" 6 March 2018

- Cover Story – February 2018: Paradise, promises and perplexities 5 February 2018

- Cover Story – January 2018: I'll be there for you, 2 January 2018

- Cover Story – December 2017: "Tabet's Tapline trajectory", 4 December 2017

- Cover Story – November 2017: "Mining negative monuments: Ângela Ferreira, Stone Free, and The Return of the Earth", 1 November 2017

- Cover Story – October 2017: Geologic Time at Stanley Glacier 11 October 2017

- Cover Story – September 2017: Dark Disruption. David Mutiloa's 'Synthesis' 1 September 2017

- Cover Story – August 2017: Walden 7; or, life in Sant Just Desvern 1 August 2017

- Cover Story – July 2017: 4.543 billion 3 July 2017

- Cover Story – June 2017: Month Light–Absent Forms 1 June 2017

- Cover Story – May 2017: S is for Shale, or Stuart; W is for Waterfall, or Whipps 1 May 2017

- Cover Story – April 2017: Banff Geologic Time 3 April 2017

Cover Story—February 2018: Paradise, Promises and Perplexities

Mon, Feb 5 2018The February 2018 Monthly Cover Story "Paradise, Promises and Perplexities" is now up on www.lttds.org – after this month it will be archived here.

"This month marks ten years since the opening of Greenwashing, curated by Latitudes and Ilaria Bonacossa. Subtitled Environment: Perils, Promises and Perplexities, this exhibition at the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin, addressed the melding of corporate agendas and individual ethics in the wake of the exhaustion of traditional environmentalism." Continue reading

Cover Stories' are published on a monthly basis on Latitudes' homepage and feature past, present or forthcoming projects, research, writing, artworks, exhibitions, films, objects or field trips related to our curatorial activities.

—> RELATED CONTENT:

Archive of Monthly Cover Stories

Cover Story – January 2018: I'll be there for you, 2 January 2018

Cover Story – December 2017: "Tabet's Tapline trajectory", 4 December 2017

Cover Story – November 2017: "Mining negative monuments: Ângela Ferreira, Stone Free, and The Return of the Earth", 1 November 2017

Cover Story – October 2017: Geologic Time at Stanley Glacier 11 October 2017

Cover Story – September 2017: Dark Disruption. David Mutiloa's 'Synthesis' 1 September 2017

Cover Story – August 2017: Walden 7; or, life in Sant Just Desvern 1 August 2017

Cover Story – July 2017: 4.543 billion 3 July 2017

Cover Story – June 2017: Month Light–Absent Forms 1 June 2017

Cover Story – May 2017: S is for Shale, or Stuart; W is for Waterfall, or Whipps 1 May 2017

Cover Story – April 2017: Banff Geologic Time 3 April 2017

Cover Story – March 2017: Time travel with Jordan Wolfson 1 March 2017

Cover Story — February 2017: The Dutch Assembly, five years on 1 February 2017

Cover Story – January 2017: How open are open calls? 4 January 2017

In conversation for the exhibition catalogue "Limits to Growth" by Nicholas Mangan (Sternberg Press, 2016)

Mon, Oct 31 2016After much anticipation, we are elated to see (and touch!) Latitudes' five-part interview with Nicholas Mangan as part of his exhibition catalogue "Nicholas Mangan. Limits to Growth" (Sternberg Press, 2016). The publication is designed by Žiga Testen and includes newly commissioned texts by Ana Teixeira Pinto and Helen Hughes, alongside illustrations of Mangan's work and historical source material.

The five-part interview weaves together a discussion around five of his recent works ‘Nauru, Notes from a Cretaceous World’ (2009), ‘A World Undone’ (2012), ‘Progress in Action’ (2013), ‘Ancient Lights’ (2015) and his newest piece ‘Limits to Growth’ (2016) commissioned for this exhibition survey. Latitudes’ dialogue with Mangan, began around a research trip to Melbourne in 2014 and continued in the form of the public conversation event that took place at the Chisenhale Gallery, London, in 2015, as well as over Skype, email, snail mail and walks.

The publication release coincides with Mangan's eponymous exhibition survey which began in July in Melbourne's Monash University Museum of Art and just opened this past weekend in Brisbane's IMA. The show will further tour to Berlin's KW Institute for Contemporary Art in the Summer of 2017.

"Nicholas Mangan. Limits to Growth"

Publisher: Sternberg Press with the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane; KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin; and Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne.

Editor: Aileen Burns, Charlotte Day, Krist Gruijthuijsen, Johan Lundh.

Texts: Latitudes, Helen Hughes, Ana Teixeira Pinto

Design: Žiga Testen;

October 2016, English;

17 x 24 cm, 246 pages + 2 inserts, edition of 1500;

40 b/w and 102 colour ill., with colour poster and postcard Softcover;

ISBN 978-3-95679-252-6;

30 Euros.

RELATED CONTENT:

- Interview with Nicholas Mangan for his forthcoming catalogue ‘Limits to Growth’, 20 Abril 2016;

- Cover Story, July 2015: Nicholas Mangan’s ‘Ancient Lights’

- Locating Ancient Lights signs around London with Nicholas Mangan;

- In conversation with the artist Nicholas Mangan at Chisenhale Gallery, London, 7 July 2015, 19h. 22 June 2015;

- Interview 'What Lies Beneath' between Nicholas Mangan and Mariana Cánepa Luna of Latitudes, Mousse Magazine #47, February–March 2015

- Max Andrews' of Latitudes feature article 'Landscape Artist', Frieze #172, June–August 2015.

In conversation with Lucas Ihlein for Artlink Magazine

Mon, Sep 5 2016The interview, titled "1:1 scale art and the Yeomans Project in North Queensland", is preceded with an intro contextualising our conversation and how we met:

|

| Lucas Ihlein and Ian Milliss, "The Yeomans Project", field trip. Farmer Peter Clinch demonstrates the keyline irrigation channels at The Oaks Organics, Camden, NSW, 2014. Photo by Caren Florance. |

We first met Lucas Ihlein in May 2014 at the recommendation of artist Nicholas Mangan. We had been invited to Melbourne to participate in Gertrude Contemporary’s Visiting Curator Program in partnership with Monash University of Art Design & Architecture, and had taken a few days out to visit the Biennale of Sydney and meet some Sydney-based artists. Nicholas was already familiar with our curatorial interests, stemming from ecology and site-specific practices; indeed, we’ve recently made an extended interview with him for the catalogue of his exhibition "Limits to Growth", so his matchmaking with Lucas was prescient. We talked for hours and have been corresponding ever since, with a view to collaborating further.

We were struck by the breadth and enthusiasm of Lucas’s practice and his voracious approach to the process of learning from the point of view of a novice. Where other people might pain over the policing of the roles of artist, curator or researcher, Lucas happily didn’t spend much time worrying about it. Accordingly, although it was the engagement with social and environmental ecology that initially piqued our interest, we soon realised that his was a collaborative practice that has embraced, for example, the re-enactment of “expanded cinema” works from the 1960s and 1970s (in the form of Teaching and Learning Cinema, run with Louise Curham) as well as a “blogging as art”, an approach that really chimed with our project for The Last Newspaper for which we had edited a weekly newspaper within an exhibition.

Indeed, a key impulse of our approach to the projects we have undertaken as Latitudes around art and ecology, in the broadest sense, has been to resist the narrow restraints of normative environmental-concern ecology, in part following Felix Guattari’s essay "The Three Ecologies" (2000), to encompass social and political relations, human subjectivity as well as historical research. In other words, thinking about a practice that does not necessarily give primacy to exhibition‑making as well as considering what an ecological art project might mean in terms of process and site, and thinking through what acting ecologically might entail in relation to acting curatorially, acting editorially, or acting historically, and so on.

Looking back on our projects in collaboration with the Royal Society of Arts “Arts & Ecology” programme—a public commission for London with artist Tue Greenfort (2005–8), our publication "Land Art: A Cultural Ecology Handbook" (Royal Society of Arts/Arts Council England, 2006), and the symposium of “Art, Ecology and the Politics of Change”, 8th Sharjah Biennial (2007)—as well as the exhibition "Greenwashing. Environment: Perils, Promises and Perplexities", Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin (2008), they now seem to belong to a very specific time when green issues gained wider traction. One might crudely say this began with the Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change in 2006 and effectively ended, or was overshadowed, by the 2008 financial crisis and its grim legacies.

We begin this interview at a moment when we’re revisiting some of the concerns left in the wake of such projects from the near past while preparing a group exhibition for CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux in 2017 around the carbon cycle and narratives of raw materials. At the time of writing Lucas has just returned from Guangzhou, where he has been exploring the geographical and social dimensions of sea level rise in the Pearl River Delta.

Continue reading...

Lucas Ihlein is an Australia Council for the Arts Fellow in Emerging and Experimental Arts. He is currently showing alongside Trevor Yeung (Hong Kong) in Sea Pearl White Cloud 海珠白雲 at 4a Centre for Contemporary Asian Art until 24 September 2016. Ihlein’s collaborative project Sugar vs the Reef will culminate in an exhibition at Artspace Mackay, Queensland, in mid-2018.

RELATED CONTENT:

- Lucas Ilhein website.

- Archive of texts written by Latitudes.

- Interview with Nicholas Mangan for his forthcoming catalogue ‘Limits to Growth’ 20 April 2016.

Interview with Nicholas Mangan for his forthcoming catalogue ‘Limits to Growth’

Wed, Apr 20 2016The five-part interview weaves together a discussion of his recent works ‘Nauru, Notes from a Cretaceous World’ (2009), ‘A World Undone’ (2012), ‘Progress in Action’ (2013), ‘Ancient Lights’ (2015) and his newest piece ‘Limits to Growth’ (2016), to be premiered at Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA). Part of an ongoing dialogue with Mangan, it developed from a public conversation event at Chisenhale Gallery, London on 7 July 2015.

‘Limits to Growth’ references a 1972 report commissioned by the Club of Rome that analysed a computer simulation of the Earth and human systems: the consequences of exponential economic and population growth given finite resource supplies. The overlapping themes and flows of energies in the five of Mangan’s projects discussed in the interview might be read as an echo of the modelling and systems dynamics used by the simulation to try and better understand the limits of the world’s ecosystems.

Mangan is presenting ‘Ancient Lights’ (2015) at his Mexico City gallery LABOR on April 22, a work co-commissioned by Chisenhale Gallery in London and Artspace in Sydney.

RELATED CONTENT:

- Latitudes conversation with Nicholas Mangan on 7 July 2015 at Chisenhale Gallery, London;

- Cover Story, July 2015: Nicholas Mangan’s ‘Ancient Lights’;

- Locating Ancient Lights signs around London with Nicholas Mangan;

- Max Andrews, Feature on Nicholas Mangan, 'Landscape Artist', Frieze, Issue 172, Summer 2015;

- Mariana Cánepa Luna, 'What Lies Underneath', interview with Nicholas Mangan, Mousse Magazine #47, February–March 2015.

Witte de With and Spring Workshop's 'Moderation(s)' publication 'End Note(s)' is out!

Thu, Mar 5 2015Latitudes participation took place in January 2013 with a month-long residency at Spring Workshop, Hong Kong, and with the production of "Incidents of Travel": an invitation extended to four Hong Kong-based artists – Nadim Abbas, Ho Sin Tung, Yuk King Tan, and Samson Young – to develop day-long tours, thus retelling the city and each participant’s artistic concerns through personal itineraries and waypoints.

As announced a few months ago, Latitudes has contributed to the publication with a visual essay documenting each of the artists' itineraries accompanying them with a revised and re-edited version of the May 2013 conversation with curator Christina Li (Moderation(s)' witness).

Here's an excerpt of our conversation with Christina:

Christina Li: The artists' tours were meant for you both to converse privately with each selected artist while getting to know their practices and the city. Did the public aspect of the Nadim Abbas' tour and your experience of the commercial tours suggest a different perspective of how the format could function from your initial perception? How has this attempt challenged your thinking in mediating and presenting the immediate experience and documentation of these tours to a larger audience?

Latitudes: Although the commercial tours were taking place regularly by prior arrangement, we happened to be the only participants on each of the days [Feng Shui tour and Tour of the Devil's Peak]. We tried to keep the artist tours casual and inconspicuous and to respect the notion of hospitality and privacy in the same way that if we came to your house for dinner, you would not expect us to bring a group of strangers with us. In fact, the day with Yuk King Tan concluded with a household of Filipina domestic workers making food for us – women whose trust and friendship she had earned through her personal affiliations and the concerns of her art. In this case, it would obviously have been completely inappropriate and something of a human safari to bring along an audience.

But we had no desire to make the days exclusive or private as if they were some kind of bespoke tourist service. Other people sometimes joined for parts of the days if the artist had suggested it, yet the main point of emphasis was our commitment to the tour in lieu of the typically brief studio visit and a situation in which the artist has had ownership of planning the whole day. If there would be definitely something like an audience present throughout (that might expect to be engaged or come and go) the dynamics and the logistics would have changed.

The artist tours were conceived from the point of view of research, and we have been reluctant to burden the artists or overload the format to the degree that they become durational artworks or somehow theatrical. We are not particularly focused on tidying up whatever their ontological status as art might be and likewise, we have deliberately not just invited artists whose work has a clear sympathy with performative, urban research or an obvious relation with sociability or place. We feel it is important that the format is quite malleable to the personality of each artist and that in the same way that you might browse a newspaper or share a car journey with somebody, the tours do not require a wider audience to legitimize them. In the same sense, they have not necessarily required documentation to make them valid. However, we have been increasingly interested in the idea of reportage or live broadcast in terms of the ‘making of’ or ‘artist at work’ genre, while at the same time being really wary about our own positions as protagonists and photographs that might seem like they belong in a travel magazine.

The tours in Mexico City took place for five consecutive days right after our arrival, so the way we shared the photographic material was more direct via our Facebook page at the end of each day. The exhibition at Casa del Lago opened only two days after we concluded the last tour, so we had to come up with a straightforward display form. For each tour, the photographer Eunice Adorno accompanied us and in the end, we projected a selection of 200 of her images as a slideshow and displayed a few of them printed on the wall alongside a large map of the city with pins locating the sites we visited. We also had printed itineraries, written by the artists, so anyone could later follow the routes themselves if they so desired.

In Hong Kong, we were using Twitter, Instagram, and Vine during the tours, so it was an experiment in documentation-on-the-fly and live journaling which was open to real-time responses. We also made a series of one-minute field recordings. The tweets were archived soon after alongside these recordings, as well as related Facebook posts. We also published blog posts about each of the tours which included many photographs (by us and others) alongside paragraphs from the artists’ itineraries. This might seem to highlight merely mundane technical aspects of the project but it also heightened our interest in further exploring the idea of the curatorial bandwidth beyond exhibition making, something we continued to investigate in following projects such as #OpenCurating.

'End Note(s)' Colophon:

Concept: Heman Chong

Editors: Defne Ayas, Mimi Brown, Heman Chong, Amira Gad, Samuel Saelemakers

Contributors: A Constructed World, Nadim Abbas, Defne Ayas, Oscar van den Boogaard, Mimi Brown, Heman Chong, Chris Fitzpatrick, Amira Gad, Travis Jeppesen, Latitudes, Christina Li, Guy Mannes-Abbott, Samuel Saelemakers, Aaron Schuster

Copy Editors: Janine Armin, Marnie Slater

Production: Amira Gad, Samuel Saelemakers, Heman Chong

Design: Kristin Metho

Printer: Koninglijke Van Gorcum

Publisher: Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art Rotterdam, the Netherlands

ISBN: 978-94-9143-529-4

RELATED CONTENT:

First week of the "Moderation(s)" residency at Spring Workshop, Hong Kong (17 January 2013)

Nadim Abbas' "Incidents of Travel: Hong Kong" public tour (19 January 2013)

"Temple and Feng Shui Tour", a guided walk around Hong Kong Island & Kowloon (22 January 2013)

Ho Sin Tung "Incidents of Travel: Hong Kong" tour (30 January 2013)

Yuk King Tan's "Incidents of Travel: Hong Kong" tour (3 February 2013)

Tour of Devil's Peak and the Museum of Coastal Defence (6 February 2013)

Samson Young's "Incidents of Travel: Hong Kong" tour (7 February 2013)

Latitudes' Open Day at Spring Workshop on 2 February 2013 (9 February 2013)

"Archive as Method: An Interview with Chantal Wong, Hammad Nasar and Lydia Ngai" of the Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong. Concluding #OpenCurating interview (1 May 2013)

"Digression(s), Entry Point(s): An interview with Heman Chong", Singapore-based artist, curator, and writer. Eighth in the #OpenCurating research series. (4 April 2013)

Archive of social media posts related to "Incidents of Travel" tours and photo-documentation.

13 field recordings from 'Incidents of Travel: Hong Kong'

Witte de With opens the group show "The Part In The Story Where A Part Becomes A Part Of Something Else" on May 22, 2014 (21 April 2014)

Interview between Christina Li and Latitudes on 'Incidents of Travel' for Witte de With's 'Witness to Moderation(s)' blog (7 May 2013)

–

This is the blog of the independent curatorial office Latitudes. Follow us on Facebook and @LTTDS.

All photos: Latitudes | www.lttds.org (except when noted otherwise in the photo caption).

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Interview with Nicholas Mangan in Mousse Magazine #47, February–March 2015

Wed, Feb 11 2015The interview centers primarily on discussing the artists' methodologies through two of Mangan's recent works: 'A World Undone' – currently on view as part of Witte de With's show 'Art in The Age of...Energy' (23 January–3 May 2015) – and his film and sculptural work 'Nauru - Notes From A Cretaceous World' which will soon be featured as part of the New Museum's 2015 Triennial: Surround Audience curated by Lauren Cornell (Curator, 2015 Triennial, Digital Projects and Museum as Hub) and artist Ryan Trecartin.

Read the full review here. Following is an excerpt of the beginning of their conversation:

NM: As transformation is a process occurring in time, the necessity to explore duration has led me to test moving image as a sculptural possibility, to express not only the temporality of the assemblage, but also the forces and drives that produce such aggregations. In the video ‘Nauru: Notes from a Cretaceous World', narration sits over found footage and material that I shot myself, providing an account of Nauru’s material history as shaped by anthropogenic forces. The narration attempts to draw out the various histories that are embedded in material forms. In more recent projects, such as ‘A World Undone’ (2012) and ‘Progress In Action’ (2013), I have attempted to produce an intensified intersection between moving image and sculpture, enabling the materials to narrate themselves.

Mangan works with LABOR (México DF), Sutton Gallery (Melbourne) and Hopkinson Mossman (Auckland).

Related Content:

Visiting Curator Program, Gertrude Contemporary, Melbourne, 12 May–7 June 2014 (28 April 2014).

'Nice to Meet You – Erick Beltrán. Some Fundamental Postulates' by Max Andrews on Mousse Magazine #31 (30 November 2011)

Interview 'Free Forms' with Lauren Cornell part of Latitudes' 2012–13 long-term research #OpenCurating, released on April 2013 via Issuu.

This is the blog of the independent curatorial office Latitudes. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

All photos: Latitudes | www.lttds.org (except when noted otherwise in the photo caption).

Work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.